Skip to content

Reading Group Guide:

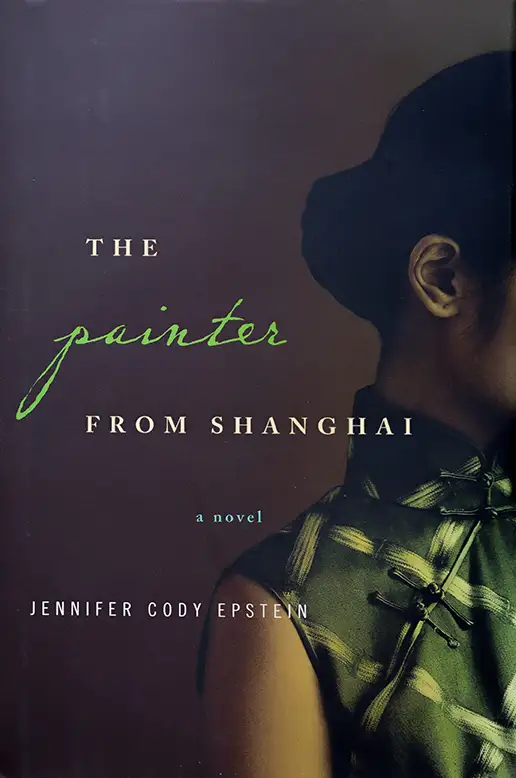

The Painter from Shanghai

- What happened to Yuliang’s mother and father? How are Yuliang’s experiences of family and intimacy shaped by her Uncle Wu and, later, her life in the brothel?

- In rendering Yuliang’s years working as a prostitute, Epstein depicts the intersection of the sexual economy, the business elite, and political leadership. How do the intrigues of the brothel affect the economy and government in Wuhu?

- How does poetry play a role in Yuliang and Zanhua’s relationship? How does their shared appreciation for poetry stand in contrast to their feelings about visual art?

- Yuliang’s budding talent for sketching is not revealed until chapter sixteen. Do earlier chapters contain any hints of her artistic abilities?

- How is Shanghai different than Wuhu? How does Yuliang’s life change after she moves to Shanghai?

- What results from Yuliang’s confrontation with the women in the bathhouse in chapter twenty-four? What does this scene reveal about Chinese female society— and what does it reveal about Yuliang?

- Teacher Hong instructs Yuliang to “see the skin as more than simply skin.” Jingling, as she mentors Yuliang in the brothel, advises her protégée to remember that “it’s just skin.” Whose advice does Yuliang follow, and why? Why is painting nude figures important for Yuliang?

- How does politics play a role in the story? To what extent is Yuliang a political person?

- Both Xudun and Zanhua have strong feelings about politics and government in China. What two ideologies do these men represent? Are they entirely opposed?

- In the 1920s and ‘30s Shanghai was often called “the Paris of the East.” As depicted in the novel, how does Shanghai compare with the French capital? Both cities are cosmopolitan, but in different ways. How do you see those differences?

- Why does Yuliang demand an abortion? Do you think she comes to regret that decision?

- How does the course of Yuliang’s personal and artistic career compare with that of her mentor, Xu Beihong?

- In chapter thirty-three, when Xudun takes Yuliang to the top of Notre Dame Cathedral—in what seems to be one of the most exciting and romantic moments of Yuliang’s life—her thoughts return to her uncle, who sold her into prostitution. Yuliang, however, frequently professes a desire to stay “rooted in the present.” To what extent is she able to do that? How do the wounds of her past manifest themselves later in Yuliang’s life? How do they affect her art?

- After she moves to Nanjing—after years in Paris and Rome and a stint as an outspoken teacher at the Shanghai Art Academy—why does Yuliang submit to acting as “the second woman” to Guanyin in Zanhua’s household? Why does Yuliang feel sympathy for Zanhua’s first wife? Do you think Guanyin deserves sympathy?

- “It is hard to find heroes in times such as these,” says Qihua, referring to Zanhua. After all that is revealed about him later in the book, does Zanhua emerge as a hero in this story? Does Xudun? Had Xudun lived, do you think Yuliang would have chosen him over her husband? Would you want her to?

- In moving back to Paris, Yuliang chooses a life of free artistic expression over a more traditional life of marriage. The last chronological scene in the novel is the prologue. Based on that opening scene, how do you think Yuliang views her life’s choices? How do you view them? Having finished the book, how has your feeling about her life and character changed? Why do you think Epstein chose to begin the novel with this scene?

- At the end of her life, Pan Yuliang had become known in her Paris circle as the “Woman of Three ‘No’s” for her steadfast refusal to work with dealers, take French citizenship, or enter into love affairs. Why do you think she was so firmly against each of these things? Are they in keeping with the image of her you’ve formed from reading The Painter of Shanghai?